Learn and Reflect with Us

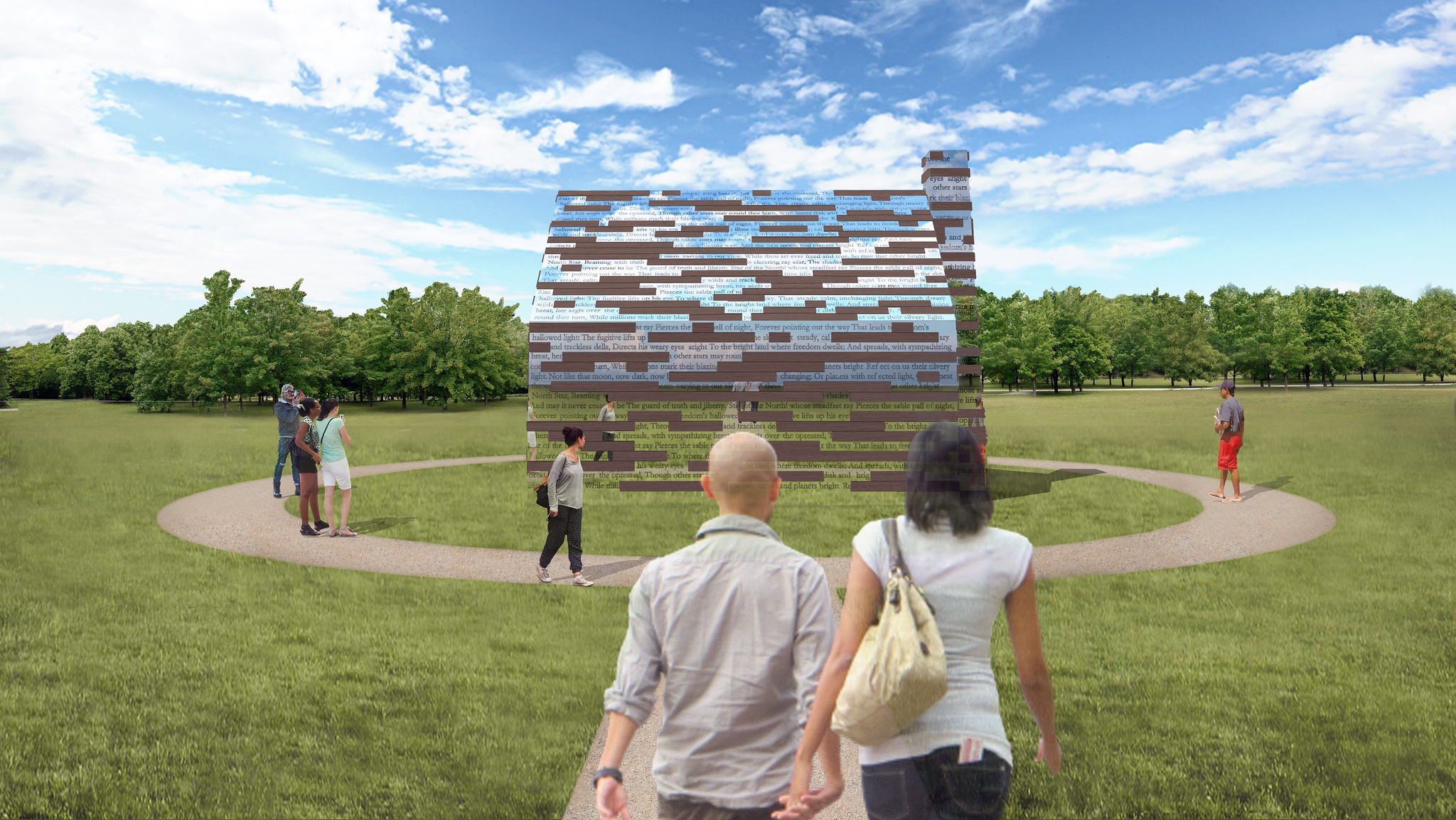

So we may better understand the world in which we live, it is important to learn from and reflect upon the experiences of people who were enslaved and had to fight for their freedom.

Visit the Commemorative

Located in one of the original thirteen colonies and on the site of Maryland’s first capital, St. Mary’s College of Maryland is steeped in this country’s early history. To preserve the physical evidence of this history, archaeological surveys are conducted prior to the start of any construction project.

Dr. Julia A. King, professor of anthropology at St. Mary’s College, her staff, and students conducted an archaeological investigation beginning in the summer of 2016 before construction of the new Jamie L. Roberts Stadium. Through this investigation, the archaeological team uncovered ceramics, bottle glass, tobacco pipes, and other artifacts from the 18th and 19th centuries. These artifacts indicated houses once stood in this location. Since the dwellings of the landowners were known, that left only two possibilities for the people who lived on this spot: enslaved or tenant families. By comparing the materials found at this site with materials found at other archaeological sites in the region, the team concluded that the proposed stadium site was once the location of slave quarters.

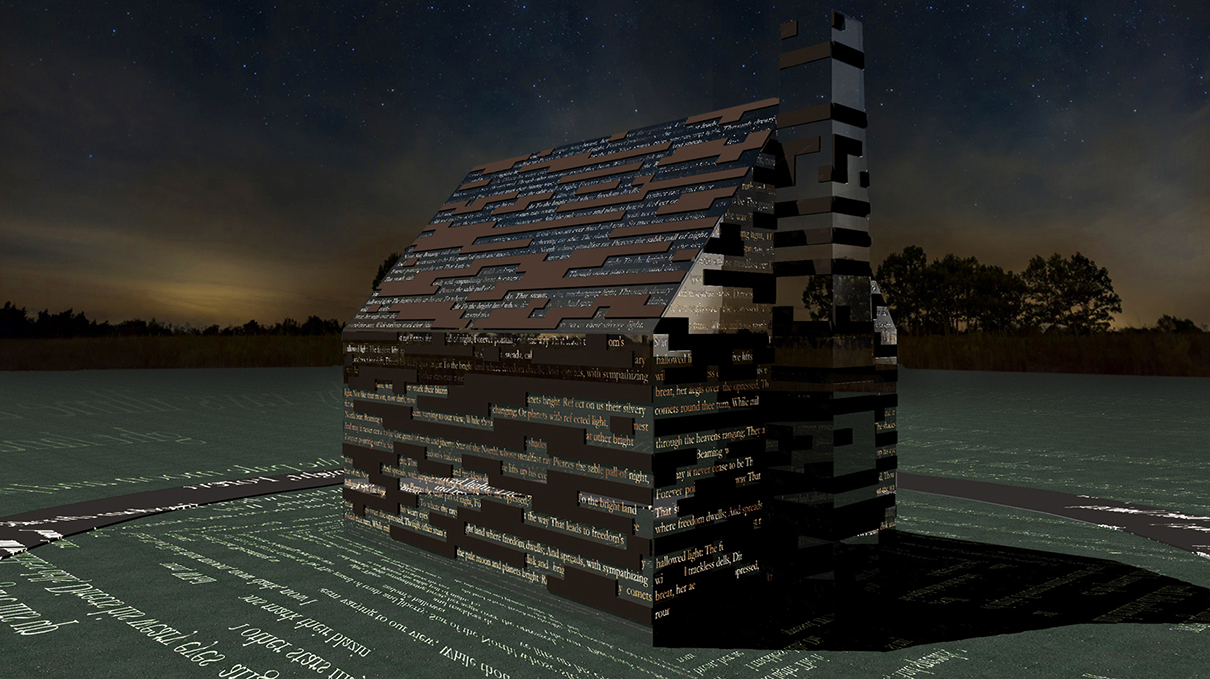

ABOUT THE COMMEMORATIVE

Learn and

Reflect with Us

So we may better understand the world in which we live, it is important to learn from and reflect upon the experiences of people who were enslaved and had to fight for their freedom.

VISIT THE COMMEMORATIVE

The Discovery

Dr. Julia King and her students did not know what they would find when they began to dig. In fact, they were not sure they would find anything at all. However, they discovered much more than anyone expected: “As we started picking up ceramics and tobacco pipes and nails and fragments of brick, we knew we had something.”

The discovery of the slave quarter complex spurred St. Mary’s College Archivist, Mr. Kent Randell to conduct separate research of historical tax records and census data to determine the College’s history with the slave trade. Through this research, Randell uncovered evidence that St. Mary’s Female Seminary utilized the enslaved labor of six people in 1850. While the archaeological discovery reconfirmed Southern Maryland’s history with the slave trade, Randell’s research established, for the first time, the College’s participation in the institution of slavery in the United States.

Should we be surprised that there is a connection between this institution of learning and the institution of slavery? No. . . . The sad reality is that during that particular period of time, in this space, at this place, it was the normal circumstance.”

-President Tuajuanda C. Jordan

We must be stewards of this history. We must learn from and teach each other about these stories. The Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland, as well as future courses, lectures, and events, will help us to uphold this responsibility.

Slavery in St. Mary’s City and Southern Maryland

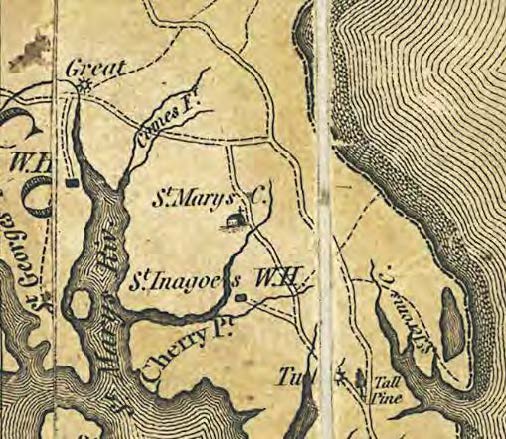

St. Mary’s College is in St. Mary’s County in a region known as Southern Maryland. Settled in 1634, St. Mary’s City was the first colonial capital of Maryland and the fourth-oldest permanent British settlement in North America.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Southern Maryland was a plantation society, which meant the region depended on hand labor to produce tobacco. Indentured European servants provided much of this labor in the 17th century, although enslaved Africans were present from the beginning. Africans became the dominant form of bound labor by the end of the 17th century. By the 18th century, enslaved Africans made up the largest portion of the labor force.

From Bondage to Freedom

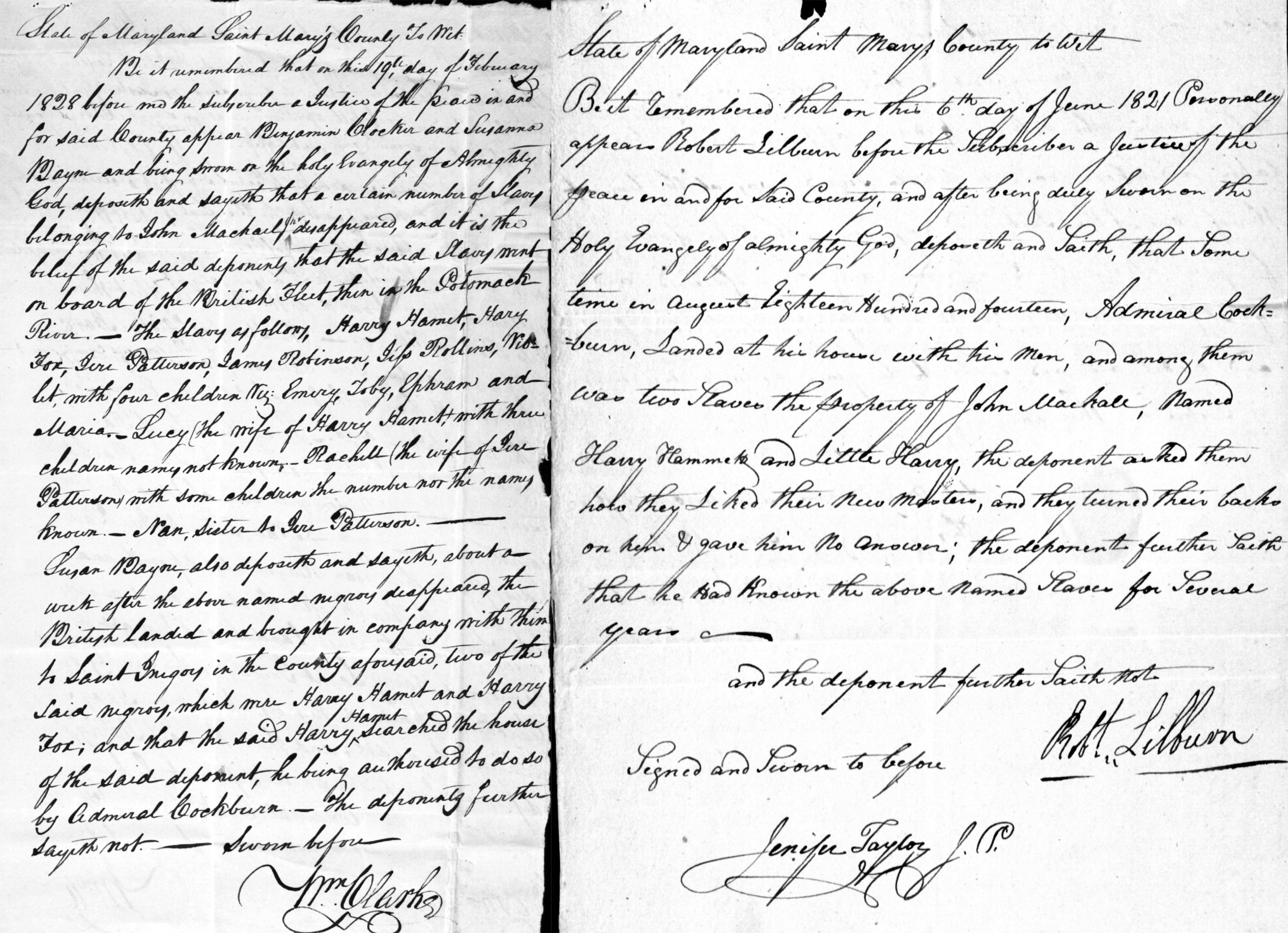

Following the War of 1812, American citizens were able to ask for reimbursements for their losses in the war. St. Mary’s College’s archives include a deposition from the Brome Plantation — the land that is now St. Mary’s College — that was written by Robert Lilburn in 1821, seven years after the end of the war. In the deposition, we learn more about some of the former slaves of the plantation who self-emancipated by joining the British.

The document says that in August of 1814, “Admiral Cockburn landed at the home of Robert Lilburn with his men. And among them were two slaves, the property of John Mackall, named Harry Hammet and little Harry. The deponent asked them, ‘How did they like their new master?’ And they turned their backs on him and gave him no answer.”

In another deposition, neighbors of Dr. Brome included a list of self-emancipated slaves — among them are Harry Hammet and Harry Fox. The deposition says that a few weeks after the slaves disappeared, the British came to the home of Benjamin Clocker and Susanna Bain with the two former slaves. Harry Hammet raided and inspected the home under the authorization of Admiral Cockburn.

These bold acts of resistance are only a few examples of how the former enslaved found redemption in their freedom — and a voice in society.

Excavation of Slavery-Related Artifacts

The archaeological survey that determined quarters for the enslaved were located in the area for the proposed stadium was a multi-faceted process. The archaeological team, led by Dr. King, viewed historical property records and then dug a series of “shovel test pits” across the field. Shovel test pits are one-foot diameter holes dug to collect artifact samples from across large areas. A geophysical survey was also conducted using ground-penetrating radar and a magnetometer (devices that measure magnetism) to identify soil anomalies beneath the ground surface.

Dr. King’s team started digging in the summer of 2016. They would not end their excavation until February 2018, following a bitter cold snap. As the project wore on, the crew became aware of the importance of their work to the college, the community, the descendants of enslaved peoples, and the history of our country.

The shovel test pits revealed six areas of archaeological sensitivity. Additionally, excavations were conducted along with continuing oral history and documentary research. Throughout this months-long process, artifacts including 18th- and 19th-century ceramics, bottle glass and tobacco pipes were unearthed. This additional work provided conclusive evidence of the presence of quarters for the enslaved.

The artifacts found in the field were typical for slave quarter sites ----- similar materials have been uncovered at other quarter sites throughout Southern Maryland. Two ceramic fragments with star-like designs, however, intrigued King and her team. King enlisted the help of her colleague and adjunct professor of anthropology, Dr. Patricia Samford, who identified the star-like motif as a recurring symbol at African American archaeological sites in Tidewater Maryland. The team also learned that ceramic fragments with a similar star-like motif had been found on the west side of Mattapany Road at a contemporary slave quarters complex.

Archaeologists believe the star-like designs found on these ceramic pieces could represent Anansi, a trickster figure in African folklore. Often taking the form of a spider, with the star-like motif representing Anansi’s web, Anansi became a symbol of resistance in the Caribbean. Perhaps enslaved people who lived here drew on Anansi to cope with their enslavement. Because these traditions were hidden from the eyes of enslavers, we may never know the true story behind the star-like design. Nonetheless, these unique ceramics provide a glimpse into the “hidden lives” of the enslaved peoples that lived in these quarters.

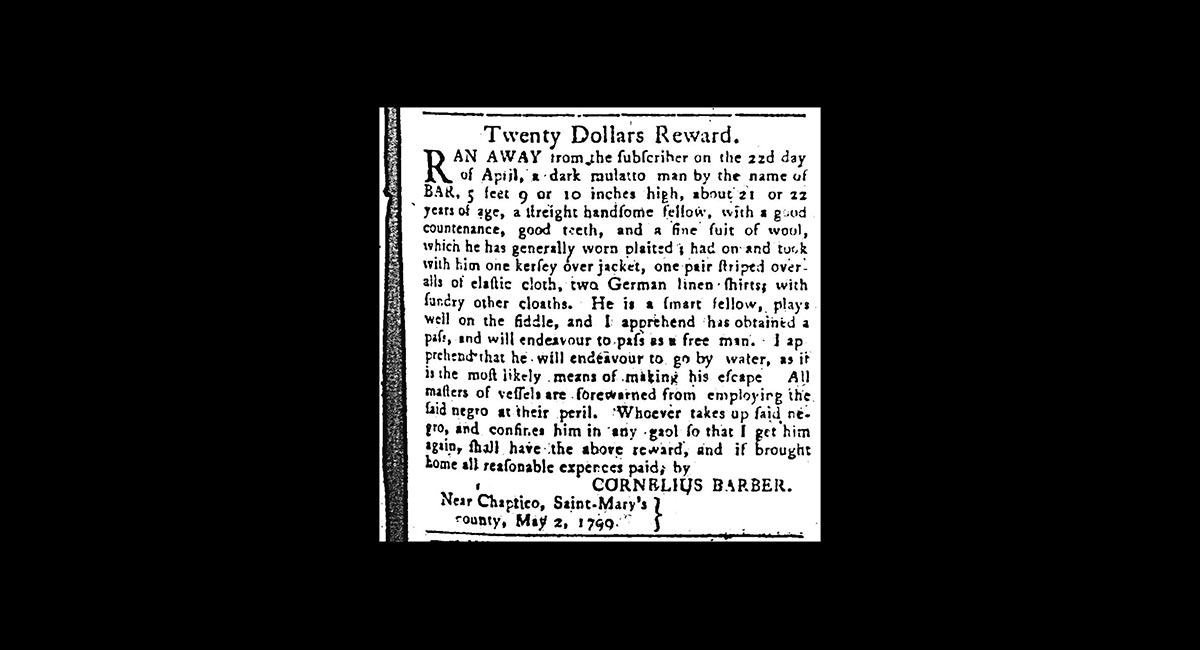

Advertising the Resistance

Historical documents provide insight and tell the stories of enslaved people. The documents reveal not only their inhumane treatment at the hands of their enslavers, but through their stories of resistance, resilience, and survival in an unjust world.

Runaway slave advertisements tell us the stories of rebellion. Each ad represents an individual who risked their life to make an attempt at freedom. Despite the chance that they would be found by bounty hunters, killed by those who enslaved them, or perished in the journey itself, they still set forth on this uncertain path.

Enslaved people also demonstrated their resistance by creating opportunities to earn an income. A Jesuit plantation, which neighbored the College, then St. Mary’s Female Seminary, kept detailed records that we have used to uncover the stories of enslaved people who built their own economies. In one diary entry, a minister wrote of the enslaved: “They were in the habit of selling some cabbages and a great many eggs. Each family raised 100, 150, or 200 chickens, which they sold at 25 cents each, seldom at a lower price. They also, in defiance of authority, gathered oysters on Sundays and holidays, which they sold to ships. The father of each family generally made $80 to $100 per year. This was clear gain to him, as he depended entirely on the (overseer) for working clothes and provisions.”

These stories provide insight into the everyday lives of enslaved people. They show that when human rights and freedoms are taken, the human spirit is resilient. That even within the confines of slavery, the enslaved found creative ways to live, to shape their own identity through participation in the consumer economy and through these efforts resist the role they were put in by those with power.

The Freedom of Water

“We have to be cognizant of how generations who walked here before us had an intimate relationship with the water that was both material, physical, religious, symbolic,” says Dr. Garrey Dennie, an associate professor and member of the Commemoration committee. “Without the water, St. Mary’s would be an entirely different place both now and in the past.”

On the land that is now St. Mary’s College, the nearby bodies of water were a resource for the enslaved. They were able to fish for their food or to sell their catch to local households, including their enslaver. Water gave enslaved people a sense of autonomy from their enslavers. And water has been an integral part of life for generations of both free and unfree people.

Leaving Home Behind

Archaeological research suggests that the slave quarters were abandoned around the War of 1812. This aligns with legal documents and personal accounts from the period that explain how and why the slaves left — often through self-emancipation by joining the British. Kent Randell shares a particular story that paints the moment in sharp relief.