Learn and Reflect with Us

So we may better understand the world in which we live, it is important to learn from and reflect upon the experiences of people who were enslaved and had to fight for their freedom.

VISIT THE COMMEMORATIVE

The Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland provides visitors with the space to acknowledge and learn from the lives of those who once toiled here, while providing a place for reflection and introspection about the nature of slavery and its connections to modern society.

Learn and

Reflect with Us

So we may better understand the world in which we live, it is important to learn from and reflect upon the experiences of people who were enslaved and had to fight for their freedom.

VISIT THE COMMEMORATIVE

Inspiration

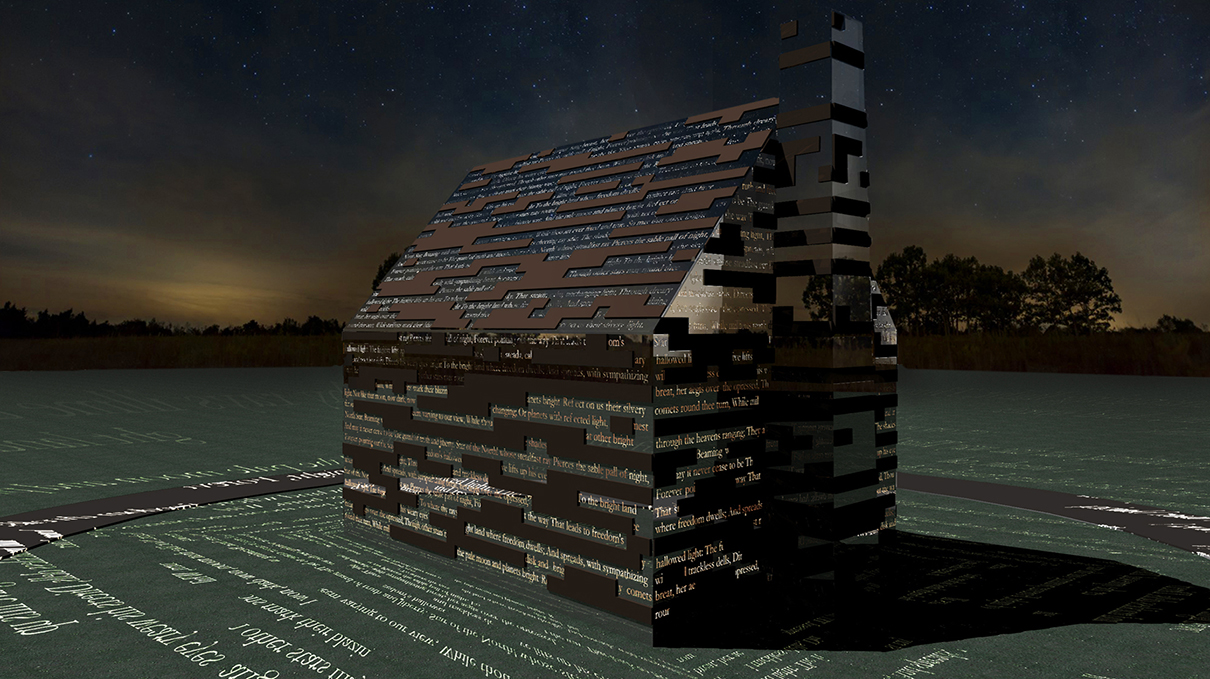

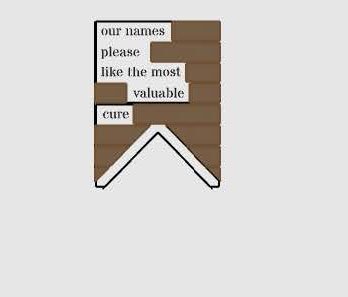

Through historical documents, archaeological research, and slave folklore, the Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland acknowledges the past while honoring the enslaved people who lived on this land, recontextualizing how we examine our shared history. The inclusion of erasure poetry on a structure inspired by the “ghost frame” architecture at Historic St. Mary’s City provides an opportunity to change the dialogue around slavery in Southern Maryland.

The “ghost frames” at St. Mary’s City provide inspiration for the Commemorative’s structure as they are not fully formed buildings but placeholders, evoking a feeling of being caught in between — in time and space. They capture the idea of transition and of incompleteness, of being here but not here. They signify a far-away past, but also suggest there is much more waiting for us to experience and understand.

A commemorative can be a reflective piece, but it can call you to action and make you think about something that is positive there. It can affect how you live your life going forward.”

-President Tuajuanda C. Jordan

Unlike a fully recreated artifact such as whole slave cabins and villages erected to provide the public with a glimpse into historical life — the Commemorative invites us to fill in the blanks. The Commemorative uses the slave quarter as a symbol of resilience, determination, and persistence. This message is reinforced by our inability to enter the Commemorative structure. As the slave quarters shielded the lives of the slaves from the enslavers, acting as both a refuge and a prison, the Commemorative too shields this private space. Not only can we not see inside but the structure reflects our gaze back on us. It does not remove us from everyday life as a historical village might, but allows us to contemplate how slavery affects us today: our biases, our legislation, how our government works, and how we as a nation deal with this very difficult past. It begs us to interpret these experiences through many different lenses.

The field and surrounding natural environment are living evidence of the plantation that once existed here. With this knowledge, the choice to build the Commemorative in this field and next to the Jamie L. Robert Stadium was deliberate. In addition to being only a few paces from where the original cabin stood, the Commemorative sits along the path that visitors use to go to games and events at the stadium. Placed where it is, it is impossible to ignore — proof that the lives the Commemorative seeks to honor are no longer buried beneath an athletic field. At night, the field acts as a canvas for the light that radiates out of the Commemorative, acting as an eternal vigil to the enslaved people who once lived, loved, worked, and resisted in this place.

Revealing the Power of Erasure Poetry

Erasure poetry is a form of found poetry that is created by erasing, or redacting, words from an existing piece of prose or verse. The redactions allow poets to create symbolism while also putting a focus on the social and political meanings of erasure. New questions, suggestions, and meanings in existing pieces of writing are revealed through erasure poetry.

The erasure poetry that covers the structure is adapted from historical documents related to the Mackall-Brome plantation — one of three known plantations located on the land around St. Mary’s City. These documents include slave property and runaway slave advertisements, newspaper articles, and slave depositions of the Mackall-Brome family. These poems become the walls and roof of the structure revealing powerful stories hidden within the language of a dark past.

Uncovering New Meaning

The Commemorative is a unique and immersive piece of art. Explore some of the poetry written by Quenton Baker that makes up the walls, roof, and chimney of the structure.

Listen to All Poems

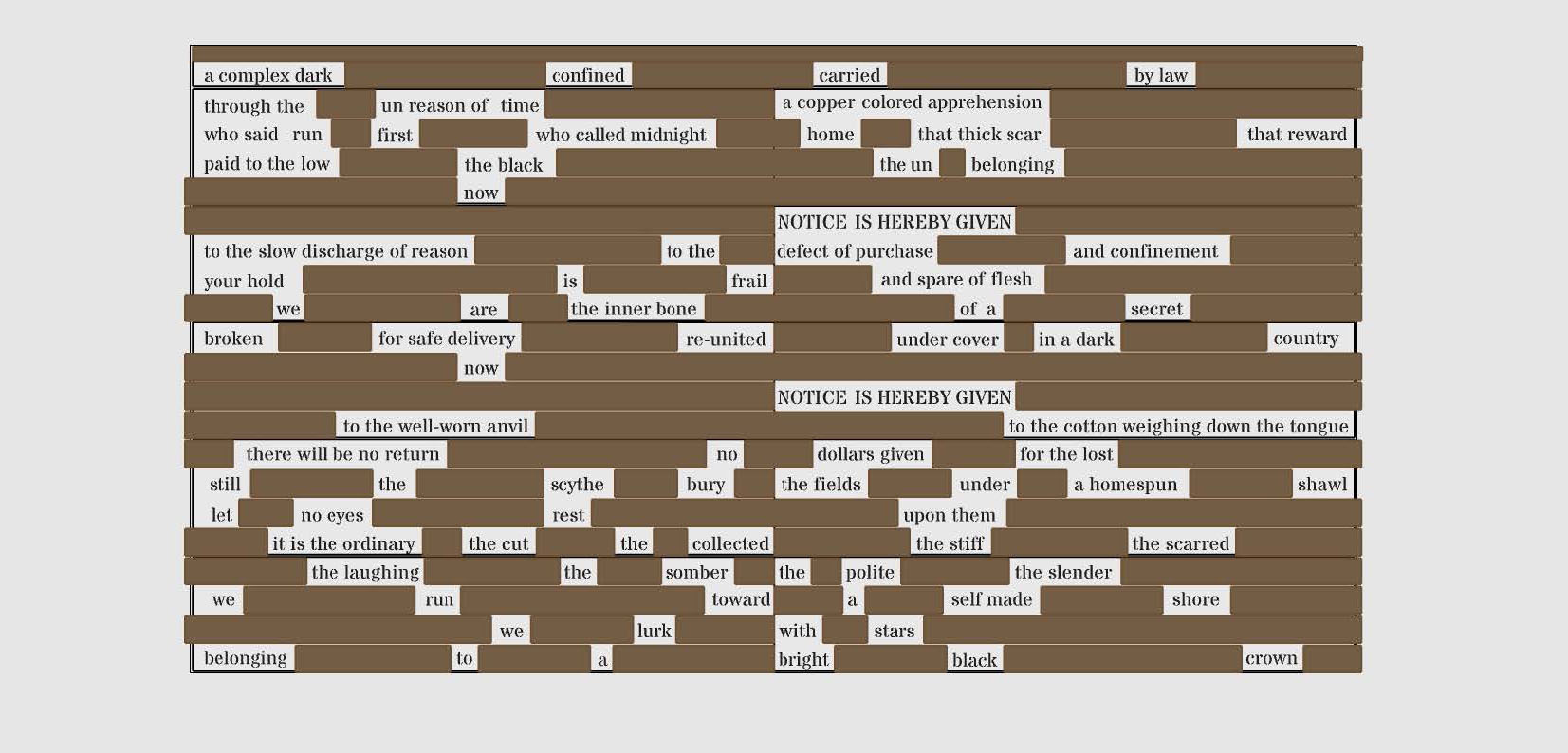

A complex dark confined- East Roof

a complex dark confined carried by law through the un reason of time a copper-colored apprehension who said run first who called midnight home that thick scar that reward paid to the low the black the un belonging now NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to the slow discharge of reason to the defect of purchase and confinement your hold is frail and spare of flesh we are the inner bone of a secret broken for safe delivery re-united under cover in a dark country

now

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN

to the well-worn anvil to the cotton weighing down the tongue there will be no return no dollars given for the lost still the scythe bury the fields under a homespun shawl

let no eyes rest upon them

it is the ordinary the cut the collected the stiff the scarred the laughing the somber the polite the slender we run toward a self made shore we lurk with stars

belonging to a bright black crown

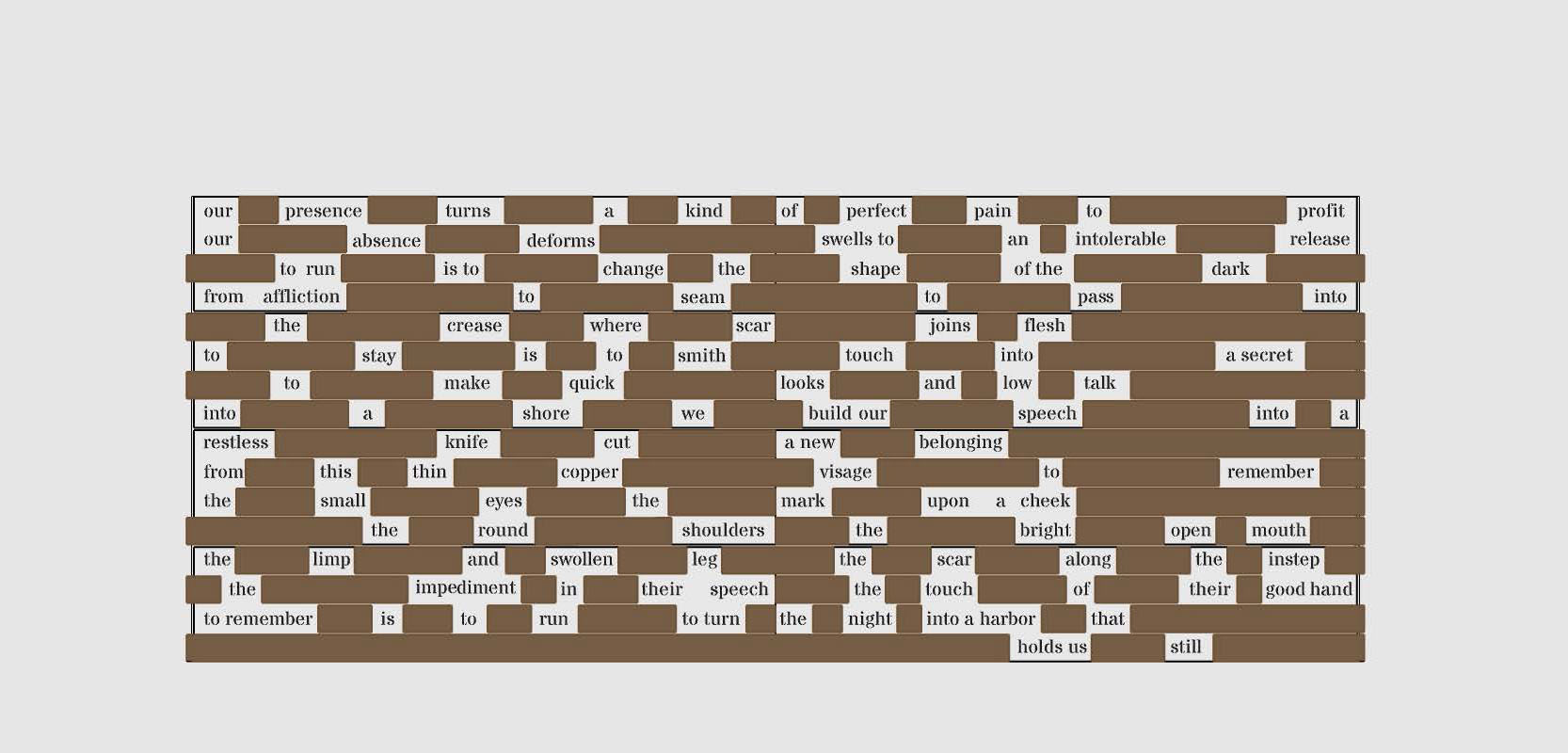

Our presence - East Wall

our presence turns a kind of perfect pain to profit

our absence deforms swells to an intolerable release

to run is to change the shape of the dark

from affliction to seam to pass into the crease where scar joins flesh to stay is to smith touch into a secret

to make quick looks and low talk into a shore we build our speech into a

restless knife cut a new belonging from this thin copper visage to remember

the small eyes the mark upon a cheek the round shoulders the bright open mouth

the limp and swollen leg the scar along the instep

the impediment in their speech the touch of their good hand

to remember is to run to turn the night into a harbor that holds us still

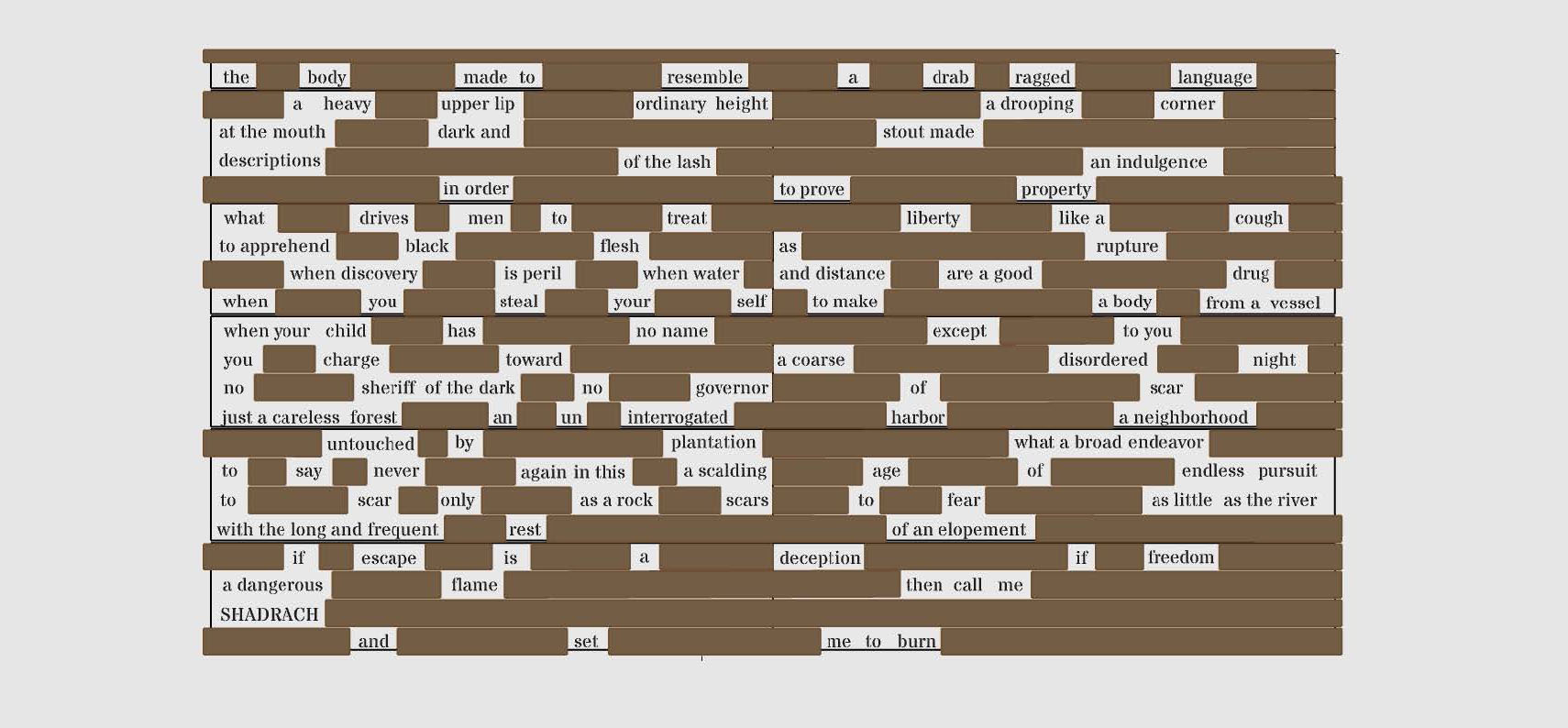

The body made to resemble - West Roof

the body made to resemble a drab ragged language

a heavy upper lip ordinary height a drooping corner at the mouth dark and stout made

descriptions of the lash an indulgence in order to prove property what drives men to treat liberty like a cough to apprehend black flesh as rupture when discovery is peril when water and distance are a good drug

when you steal your self to make a body from a vessel

when your child has no name except to you you charge toward a coarse disordered night

no sheriff of the dark no governor of scar just a careless forest an un interrogated harbor a neighborhood untouched by plantation what a broad

endeavor

to say never again in this a scalding age of endless pursuit

to scar only as a rock scars to fear as little as the river

with the long and frequent rest of an elopement if escape is a deception if freedom a dangerous flame then call me

SHADRACH

and set me to burn

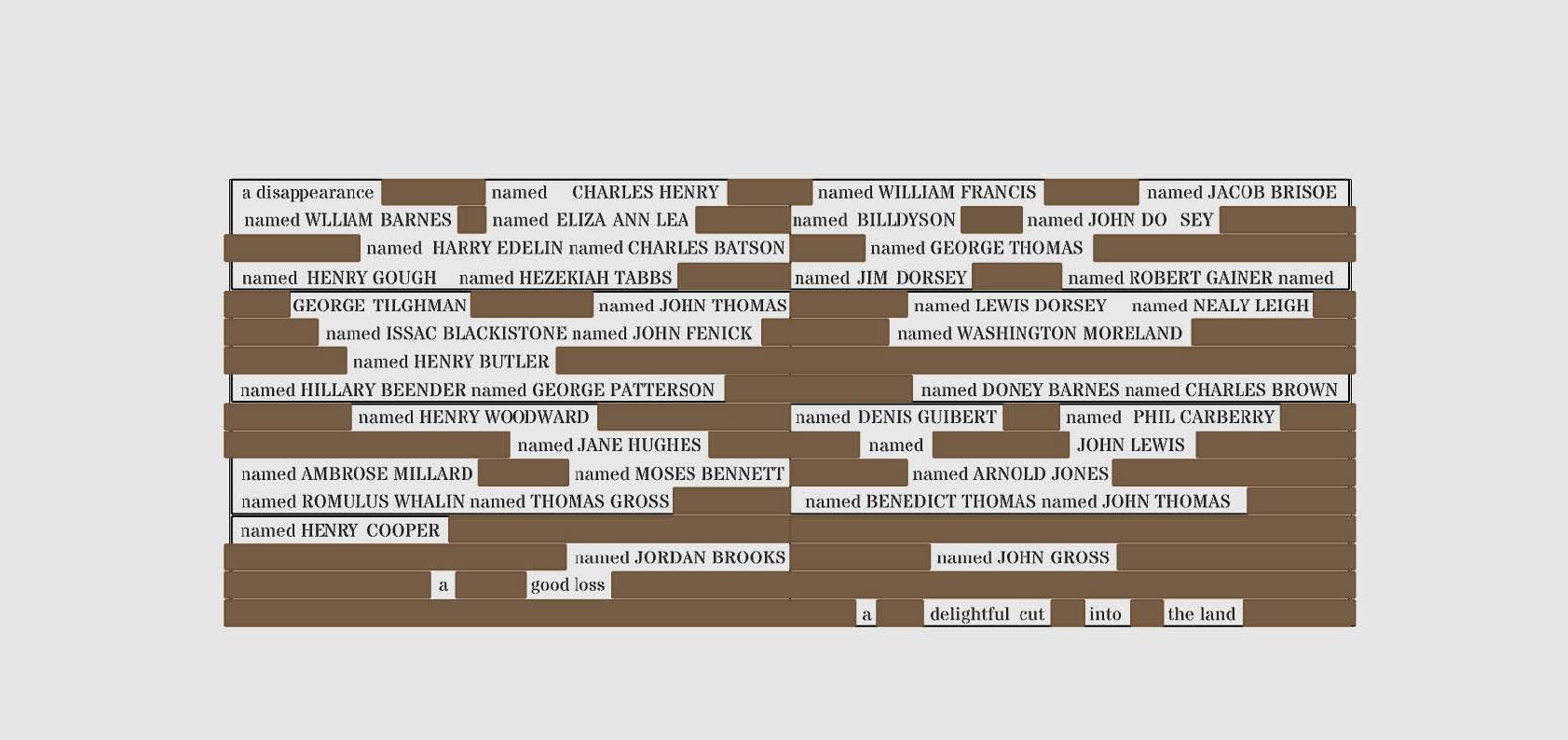

A disappearance - West Wall

a disappearance named CHARLES HENRY named WILLIAM FRANCIS named JACOB BRISCOE

named WLLIAM BARNES named ELIZA ANN LEA named BILL DYSON named JOHN DORSEY named HARRY EDELIN named CHARLES BATSON named GEORGE THOMAS

named HENRY GOUGH named HEZEKIAH TABBS named JIM DORSEY named ROBERT GAINER named GEORGE TILGHMAN named JOHN THOMAS named LEWIS DORSEY named NEALY LEIGH

named ISSAC BLACKISTONE named JOHN FENICK named WASHINGTON MORELAND

named HENRY BUTLER

named HILLARY BEENDER named GEORGE PATTERSON named DONEY BARNES named CHARLES BROWN

named HENRY WOODWARD named DENIS GUIBERT named PHIL CARBERRY

named JANE HUGHES named JOHN LEWIS

named AMBROSE MILLARD named MOSES BENNETT named ARNOLD JONES named ROMULUS WHALIN named THOMAS GROSS named BENEDICT THOMAS named JOHN THOMAS

named HENRY COOPER

named JORDAN BROOKS named JOHN GROSS a good loss a delightful cut into the land

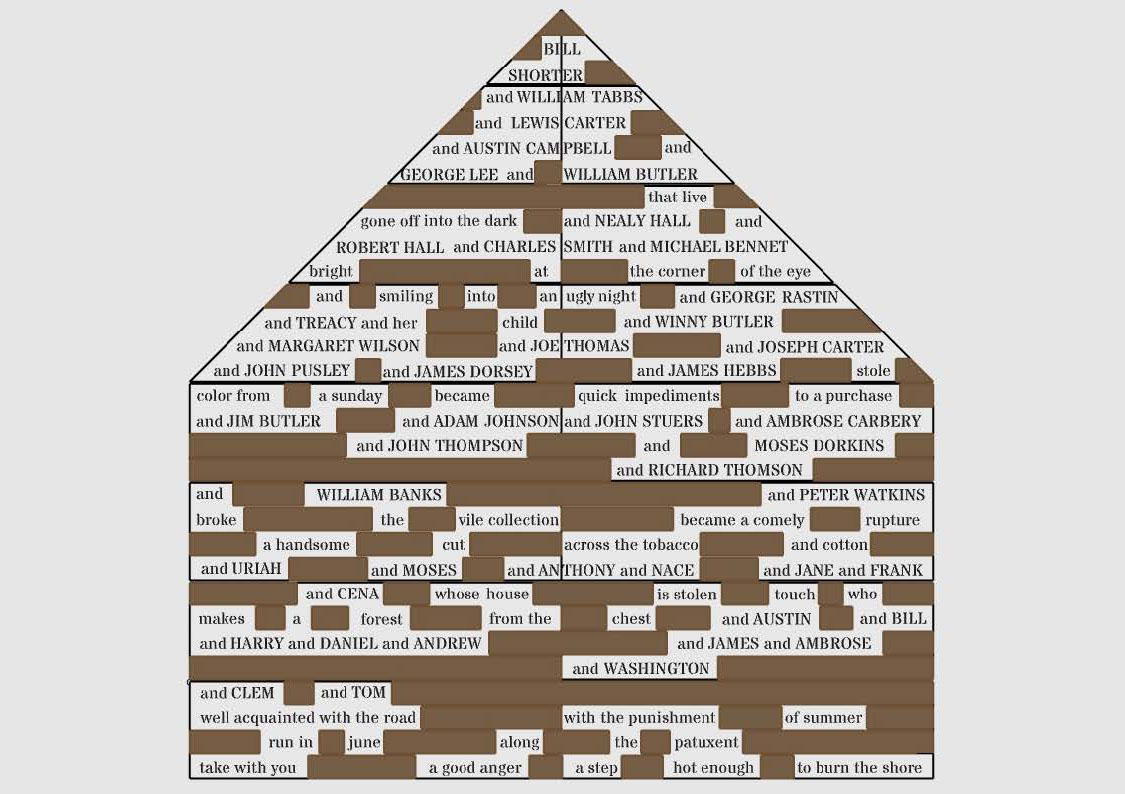

Bill shorter - North Gable

BILL SHORTER

and WILLIAM TABBS

and LEWIS CARTER

and AUSTIN CAMPBELL and

GEORGE LEE and WILLIAM BUTLER that live

gone off into the dark and NEALY HALL and ROBERT HALL and CHARLES SMITH and MICHAEL BENNET bright at the corner of the eye and smiling into an ugly night and GEORGE RASTIN and TREACY and her child and WINNY BUTLER and MARGARET WILSON and JOE THOMAS and JOSEPH CARTER

and JOHN PUSLEY and JAMES DORSEY and JAMES HEBBS stole color from a sunday became quick impediments to a purchase and JIM BUTLER and ADAM JOHNSON and JOHN STUERS and AMBROSE CARBERY

and JOHN THOMPSON and MOSES DORKINS

and RICHARD THOMSON and WILLIAM BANKS and PETER WATKINS

broke the vile collection became a comely rupture a handsome cut across the tobacco and cotton and URIAH and MOSES and ANTHONY and NACE and JANE and FRANK

and CENA whose house is stolen touch who makes a forest from the chest and AUSTIN and BILL

and HARRY and DANIEL and ANDREW and JAMES and AMBROSE and WASHINGTON

and CLEM and TOM

well acquainted with the road with the punishment of summer run in june along the patuxent take with you a good anger a step hot enough to burn the shore

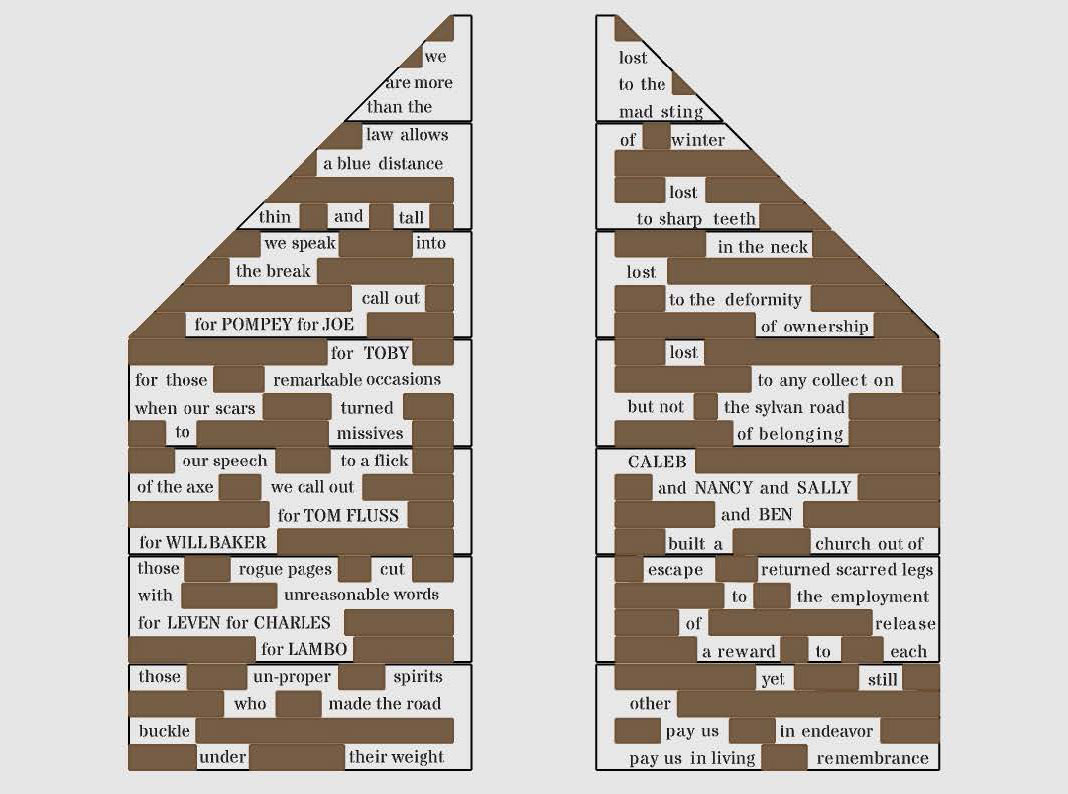

We are more - Chimney Gable

SOUTHEAST - WALL (LEFT)

we

are more than the law allows

a blue distance

thin and tall we speak into the break

call out

for POMPEY for JOE for TOBY

for those remarkable occasions

when our scars turned

to missives

our speech to a flick

of the axe we call out

for TOM FLUSS

for WILL BAKER

those rogue pages cut with unreasonable words for LEVEN for CHARLES

for LAMBO

those un-proper spirits who made the road buckle

under their weight

SOUTHEAST - WALL (RIGHT)

lost

to the

mad sting

of winter

lost

to sharp teeth

in the neck

lost

to the deformity

of ownership

lost

to any collection

but not the sylvan road

of belonging

CALEB

and NANCY and SALLY

and BEN

built a church out of

escape returned scarred legs

to the employment

of release

a reward to each

other

yet still

pay us in endeavor

pay us in living

remembrance

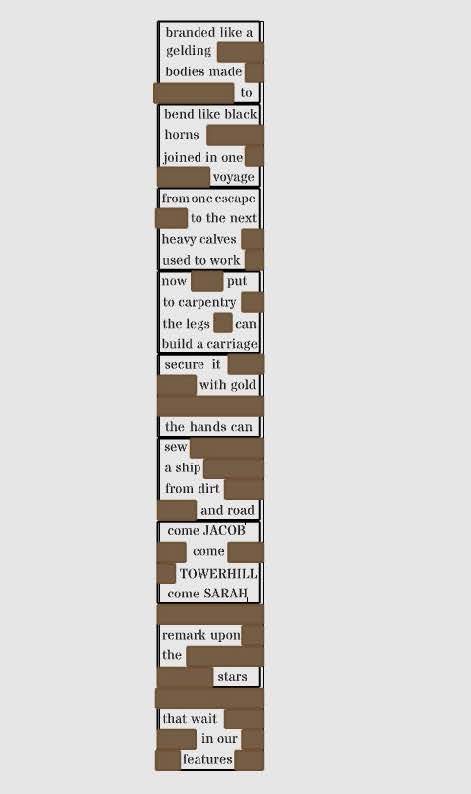

Branded like a gelding - Southwest Chimney

branded like a

gelding

bodies made

to

bend like black

horns

joined in one

voyage

from one escape

to the next

heavy calves

used to work

now put

to carpentry

the legs can

build a carriage

secure it

with gold

the hands can sew

a ship from dirt

and road

come JACOB

come

TOWERHILL

come SARAH

remark upon the

stars

that wait

in our

features

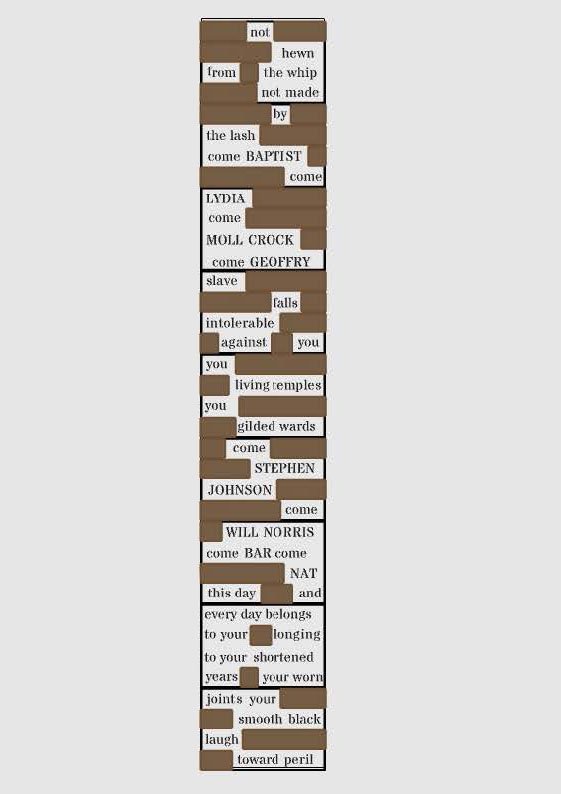

Not hewn from the whip - Southeast Chimney

not

hewn

from the whip

not made

by

the lash

come BAPTIST

come

LYDIA

come MOLL CROCK

come GEOFFRY

slave

falls

intolerable

against you

you

living temples

you

gilded wards

come

STEPHEN JOHNSON

come

WILL NORRIS

come BAR come NAT

this day and every

day belongs

to your longing

to your shortened years

your worn joints your

smooth black laugh

toward peril

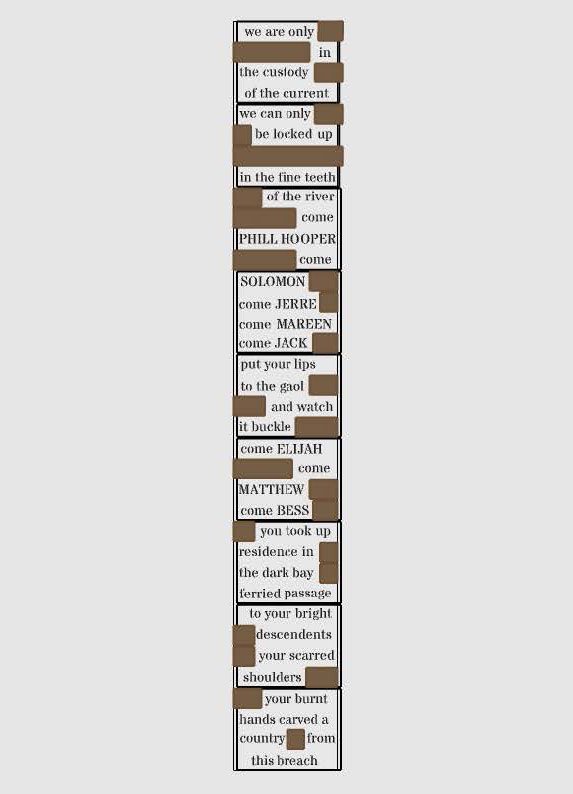

We are only - Northwest Chimney

we are only

in

the custody

of the current

we can only

be locked up

in the fine teeth

of the river

come

PHILL HOOPER

come SOLOMON

come JERRE

come

MAREEN

come JACK

put your lips

to the gaol

and watch

it buckle come

ELIJAH

come MATTHEW

come BESS

you took up

residence in the dark

bay ferried

passage

to your bright

descendents

your scarred shoulders

your burnt hands

carved a country

from this

breach

Our Names Please - Northeast Chimney

our names

please

like the most

valuable

cure

Going through the exercise of erasing certain elements of those documents, you're engaging history. You are embracing history. But at the same time, you're critiquing history.”

-Dr. Jeffrey Coleman

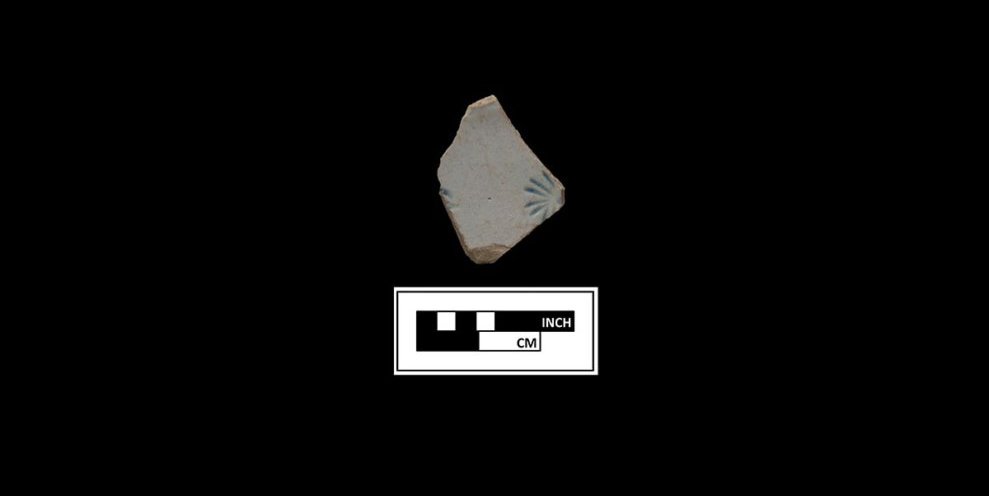

Symbols of Resistance

Illuminated from within at night, the poetry is projected onto the ground surrounding the Commemorative, mimicking the star-like pattern found on a number of ceramic artifacts discovered during the College’s archaeological investigation. This effect points to the theory discussed by experts that the star-like pattern symbolizes the web of Anansi, the African folklore character. Anansi’s web represents resistance of the plantation system and slavery in the New World. The light projecting from the Commemorative at night also serves as a beacon, or North Star, representing the journey north to lasting freedom.

We engaged in a lot of public outreach and compiled the responses of the public — both online and through presentations with the public, with the students, with the faculty and staff. Folks overwhelmingly said that they wanted a commemorative that was contemplative, that was respectful, that caused people to really stop and think.”

-Kent Randall

Focusing on Reflection

Many were surprised by the location chosen for the Commemorative. But there was a very intentional reason why it was built on land that was supposed to become athletic fields. “Because you can’t ignore it,” says President Tuajuanda C. Jordan. “When people are going through those athletic fields, it is there in their face. I want that to give them pause and wonder, why is this here?”

Honoring the Resilience of Enslaved People

Construction of the Commemorative

Through the selection process, and considering feedback from students, faculty, staff and community members, the Commemorative selection committee contracted the firm RE:site to design the Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland.

The contrast of historical and modern between the Commemoration and the new Jamie L. Roberts Stadium creates a tension, causing us to pause and reflect on the institution of slavery and how we as Americans are connected to this history.

The structure measures about 20 feet long and 15 feet deep and is encircled by a wide footpath and natural grass. Its construction was intended to stand the test of time with a steel framework clad with panels of polished mirror stainless steel and tropical hardwood. It resists weathering, rot, abrasion, and insects.

Like a lighthouse (or the North Star) the lighting system serves as a beacon, using intricate lenses and positioning to shape the light it emits. The result is an ethereal stencil of light beams, projecting the poetry on all sides.

Construction of the Commemorative to Enslaved Peoples of Southern Maryland began in July 2019. The project was completed on October 31, 2020 and opened to the public on November 21, 2020.

About the Artists

Shane Allbritton and Norman Lee are the co-founders of RE:site, an art studio that explores notions of community, identity, and narrative in the context of public space. Allbritton has 20 years of experience designing interpretive spaces and interactives for cultural institutions. She is a visual storyteller versed in a range of media, including large scale murals, sculpture painting, wayfinding and design. Lee began his career as an interpretative environment designer in 2003 and was a finalist in the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition. His work has been featured in the New York Times, USA Today, the Houston Chronicle, Art in America, and other publications.

“We envision the Commemorative connecting our lives with the lives of slaves and causing us to pause and reflect on how we as Americans are connected to this history.”In an interview with Shane Allbritton and Norman Lee, the creators behind the commemorative, they spoke of their challenge to make the commemorative as relevant to the landscape as it was to the conversations about slavery.

The Creation of a Commemorative: An Interview with the Artists

What was your creative approach in trying to give voice to the College's discovery of slave quarters and honoring the find?

Mr. Norman Lee: Our approach was to make the Commemorative as site-specific as possible. This included drawing inspiration from the archaeological research and artifacts discovered by the College, the architecture of Historic St. Mary’s City, historical documents related to the plantation, as well as the formal aspects of the site itself. Also, we wanted the Commemorative to directly engage the rhythm of daily campus life as opposed to secluded or isolated from it.

What is unique about your approach that separates this design from others honoring slavery across the country?

Ms. Shane Allbritton: Most memorials that focus on slavery across the country tend to deal with the subject broadly in in sculptural terms. Whether they are about the entire transatlantic slave trade or specific events in history, most of these memorials use a figurative approach that are interpreting themes in universal terms. In our design, we incorporate of the actual text taken from runaway slave ads placed by slave owners that once operated plantations in and around St. Mary’s City. Although the text is redacted to create poetry, the words presented are the actual words and, by definition, the voice used by the slave owners of the region and there is real site-specific power to this

How does the Commemorative you created connect the past to the present and future?

NL: The Commemorative connects the past to the present and future through reflection. When viewers engage the work, they see themselves, the activity surrounding the nearby sports stadium reflected, interlaced with poetic text, coalescing into a visually resonant sculptural experience. The Commemoration juxtaposes the current site of sports field with its slave past, holding them in dramatic tension.

What challenges did you face in bringing this project to life?

SA: The biggest challenge was finding historical documents related to the Mackall Broom and other nearby plantations that could be used to create powerful redacted or erasure poetry in the context of the design. Our collaborator, poet Quenton Baker, researched various types of documents related to the plantation site and eventually discovered hundreds of runaway slave ads that became the foundation of his poetry.

NL: We were struck by how the ads were so personally descriptive of the runaway slaves, but at the same time profoundly impersonal, as the words were coming from a context of describing property. This dichotomy was particularly resonant for us as artists because it distilled the essential inhumanity of chattel slavery in our nation’s history.

What statement do you want the Commemorative to make?

SA: We envision the Commemorative connecting our lives with the lives of slaves and causing us to pause and reflect on how we as Americans are connected to this history.

What kind of experience do you hope for those viewing it?

NL: This is a difficult question to answer as one’s experience with any work of art is highly personal and subjective and dependent on the previous life experience that the viewer brings with them. It is probably easier to say what we would not want a person to experience when viewing the Commemorative, and that would be indifference.

Are their particular aspects of this project that have special meaning for you?

SA: This project is a culmination of why we do what we do. As artists, we are drawn to commemorative and memorial projects that help communities to wrestle with complex and traumatic historical memories. Our approach to commemoration is defined by a sensitivity to the transcendent and an open, inclusive vision of our shared fate as a multiracial nation. Much of our past works engages difficult pasts, including themes of slavery, tension between police and community, and labor and civil rights struggle, in ways that tell hard truths and also reach toward a hopeful future.

NL: We are also sensitive to the reality of this critical moment in our nation’s story. We are seeing an unprecedented wave of protest in defense of Black lives, the removal of Confederate monuments and symbols around the nation, calls to make Juneteenth a national holiday, and a renewed examination of racially insensitive aspects of popular culture and media. In this context, we are humbled and honored to realize a project that contributes to this historic narrative.

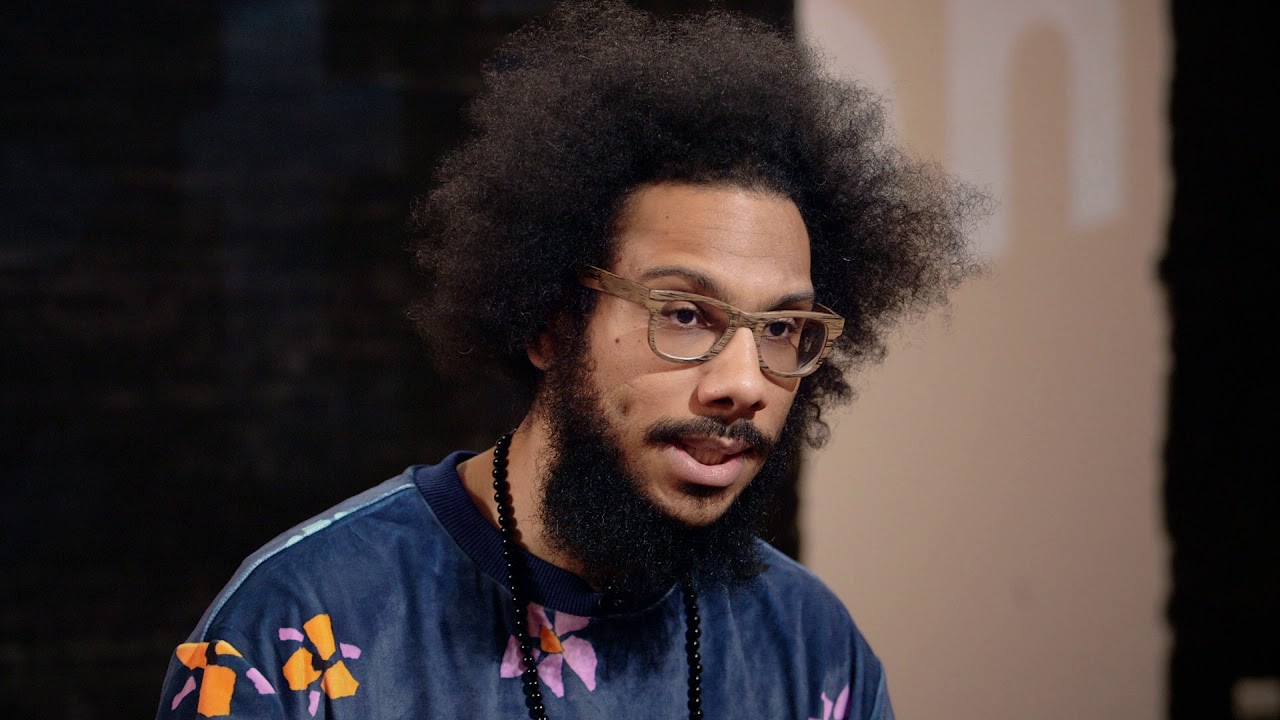

Quenton Baker is a poet, educator, and Cave Canem fellow. His current focus is Black interiority and the afterlife of slavery. Baker has an MFA in poetry from the University of Southern Maine and is a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee. His work has appeared in The Offing, Jubilat, Vinyl, The Rumpus and other publications.

“I would love the Commemorative to be a possibility, the beginning of an investigative process, a reason to ask questions about what it means to live in a country capable of starting its history as this one did, with stolen land and stolen bodies.”Commemorative poet, Mr. Quenton Baker, offered insight into his process — and his duty to amplify the voices of those who were silenced, using the words of those who silenced them.

What was your creative approach in trying to give voice to the College's discovery of slave quarters and honoring the find?

The three things that I wanted to keep in mind above all were: this is a local project and involving the community and keeping it focused on St. Mary’s County was vital; to ground whatever work that came out of this process in research, maintain a text-based approach; and to not project myself backwards through time, or to try and speak for or speak through folks, but rather to bear witness.

What is unique about your approach that separates this design from others honoring slavery across the country?

I think the classic mistake in dealing with any type of history, especially the history of enslaved people in this country, is obliterating your subject. I can’t know or imagine or deduce what it meant to be enslaved, or what it was like inside the mind and body of the people we are honoring. And I wouldn’t want to try. I believe that in trying to speak for these dead, speak for the objectified and violated, you run the risk of obliterating their positionality, as fraught and as difficult as it might have been. The stark reality is that the enslaved in St. Mary’s County were not people. They were to themselves, and they are to me, but they did not occupy that role in the time and locations they lived in. That is an impossible thing to consider and an impossible thing to understand. And yet, you have to keep it in mind. We invite erasure and, indeed, a kind of obliteration when we forget that.

How does the Commemorative you created connect the past to the present and future?

Any time we consider the slave we are connecting the past to the present and future. Slavery has been abolished, but the anti-blackness and realities of black non-being which precipitated the system of chattel slavery have not. It’s the same animus that lurked and lurks inside Jim Crow, mass incarceration, the general continued lack of access to healthcare, education, employment, safety that defines black life. We live in what Saidiya Hartman would call the “afterlife of slavery,” or what Christina Sharpe would call its wake. To consider the slave is to consider how the slave is made, and how it can, if it can, be unmade. And that consideration leads us to ask: has it? And if so, how can we explain what we see around us, what we know to be true? We cannot. And then we know our grim inheritance, that there is still a project to be completed in the present and in the future.

What challenges did you face in bringing this project to life?

The most difficult obstacle for me was the text and the subject. It’s not easy or fun to engage with chattel slavery. It’s draining, it’s damaging, it’s an endeavor. To work in the mode of erasure poetry, you have to hold the text within yourself, in a way. Letting 240 runaway slave ads live inside of you for months takes a toll.

What statement do you want the Commemorative to make?

I think about this project less as an opportunity to make a statement and more as a kind of opening. I would love the Commemorative to be a possibility, the beginning of an investigative process, a reason to ask questions about what it means to live in a country capable of starting its history as this one did, with stolen land and stolen bodies.

What kind of experience do you hope for those viewing it?

An engaged one.

Are their particular aspects of this project that have special meaning for you?

The entire project has profoundly special meaning to me. I’m honored to have been a part of it.