Earn your Bachelor of Science at our exclusive waterfront location

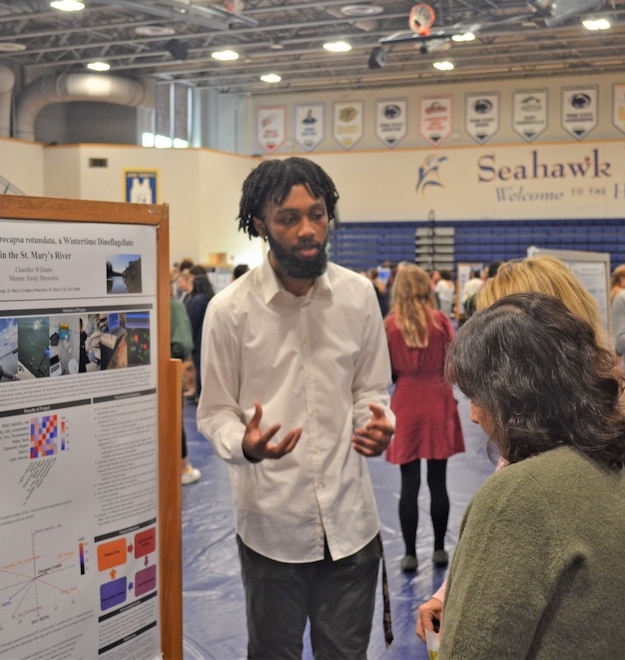

As a biology major, you’ll get to do hands-on research in our top-notch labs, on our beautiful campus, or even right in the St. Mary’s River! Many students also take their research abroad during study trips. The biology major includes a wide range of exciting courses like ecology, human anatomy, zoology, and more!

92%

of our graduates go on to post-graduate study or to work in the biological sciences

Best Colleges for Biology in Maryland

TOP 25

Hidden Gems for Women in STEM by CollegeRaptor.com

Biology Major

As a biology major, you’ll take four main courses: Principles of Biology I and II, Genetics, and Ecology and Evolution. These courses cover a wide range of biology topics and teach you how to design your own lab experiments and analyze scientific data.

To finish your biology degree, you’ll pick any four advanced biology courses, including at least two with labs. This setup gives you a solid foundation in biology while letting you explore areas that interest you.

Biology Minor

A minor in biology gives you a strong grasp of how living things work, how to do research, and how to think critically. It’s a great addition to any major, helping you understand scientific ideas and methods better.

Having a biology minor can be useful in many fields like science, social work, business, government, health care, and other industries, both in the U.S. and around the world. It can open doors in many different careers and make you stand out.

Courses Offered

Biology Courses

- Biology Courses>

HONORS COLLEGE PROMISE

Expand your learning beyond the classroom with opportunities like studying abroad, internships, hands-on classes, or independent research. These experiences help you see the bigger picture.

At St. Mary’s College of Maryland, you’ll benefit from experienced professors, unlike at larger universities where teaching assistants may lead classes. You’re more likely to have the same professor for multiple courses, work with them on your St. Mary’s Project, or have them as your academic advisor.

When you need letters of recommendation for jobs or grad school, you’ll have professors who know you well and can write strong, detailed letters. All our biology professors have Ph.D.’s and are active in research, with advanced lab equipment available for you to use. This close relationship between faculty and students makes your experience at St. Mary’s unique compared to larger schools.

"I was able to learn in a very hands-on manner because of the college's location, where I could see the processes of coastal ecology and hydrology at work right in front of me"

- RUSTIN PARE '21, BIOLOGY MAJOR

Health Sciences Advisory Committee

The Health Sciences Advisory Committee (HSAC) stands to provide advice and guidance to students interested in preparing for graduate programs in the health sciences. We advise any student from any major interested in a career in health sciences. We have worked with students as far as ten years post graduation to help them with their files.

- The HSAC holds periodic information meetings that often include a special guest visitor speaking about some element of health care or funding for graduate programs.

- The HSAC encourages students to strengthen their profiles throughout their education at St. Mary’s College so that they are strong applicants when they do apply to graduate programs.

- Students applying to medical, vet, dental, and some other programs as requested undergo a mock interview with a committee of faculty who know them best. This experience often makes a huge difference when students go on to their actual first interviews.

After you Graduate

A degree in Biology opens doors in a wide range of industries from education to business, humanitarian efforts, scientific exploration and discovery, health care, and human services and advocacy.

Our graduates are known for their responsibility; creative, critical, and analytical thinking; problem solving abilities; intellectual curiosity; and communication skills. These are attributes applied in everyday life, no matter what the person’s chosen field. They are strongly applicable in science and give our graduates advantages not necessarily gained in career-focused education.

LATEST NEWS

Connect with Your Program Chairs

All the faculty here at St. Mary's College of Maryland want to help you explore your interests and set you up for success. We look forward to connecting with you and meeting you on campus.